Part 1: TICKET TO OZ

How my longing to trace descendants of my late mother's eldest brother, who emigrated to Western Australia with his wife and children in 1912, led me into a dream adventure.

Parts 2 & 3: PERTH and FREMANTLE

Scenes I enjoyed in these two cities. To be expanded after my next visit!

Part 4: SEARCHING FOR MUNDIWINDI

..... let that page speak for itself.

Part 5: TO MARBLE BAR AND BEYOND

A journey up to Marble Bar (hottest place in Australia when it really gets going) and down the west coast of WA back to Perth.

A willy-willy, diamond mine, gold mine, overnight on a cattle station, School of the Air, aboriginal petroglyphs, stromatolites, it's all there - and more.

KALGOORLIE BIPLANE:See www.hibeach.net/biplane.html

These letters, and much more, can be seen at www.hibeach.net/bowden.html

|

PART 4 OF DOWN UNDER ADVENTURE

SEARCHING FOR MUNDIWINDI

The first part of my Oz holiday - in Perth and Fremantle - was now about to give way to a journey up to the Pilbara, iron mining country where the rusty red soil echoes the presence of the valuable ore. The thought set my pulses racing. Come Sunday morning, 2nd September, I packed my two small bags and that afternoon flew up to Newman. It had started as a closed town built in the late 1960's to house workers in the nearby Mount Whaleback iron mine (the largest open-cast iron mine in the world) and was opened up to the public only in 1981.

200 ton Haulpak in the Newman Museum

In the Pilbara, which covers an area of over 216,000 square miles/560,000 square kilometers, there are areas of deep winding gorges where paths lead you to pools half hidden amongst the trees and the silence is broken only by bird calls and the splash of waterfalls, but move further inland and it is scrub and semi-desert - the heart of Western Australia's outback. The eastern part of the Pilbara is said to be one of the most inhospitable regions in Australia. We didn't visit the gorges, time could not encompass everything, but to me the compelling draw was that outback, its ruggedness, the silence, the raw beauty. Some people are drawn to deserts and I think it is something of the same feeling.

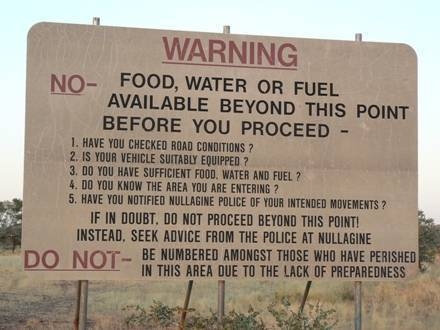

Hot, dry, dusty and full of flies for much of the year, subject to tremendous flooding in the Wet, it is inhospitable and downright dangerous if you are foolhardy enough to venture in without UHF radio and being completely self-sufficient in vehicle repair equipment, medical supplies, fuel, food and water, above all water, water, water. Never having seen anything more deserted than Minsmere beach on a bitter winter's day and never having spent a single night under canvas even in this country, I couldn't wait to be there.

Warning sign on the road to Nullagine

The young chap in the plane seat next to me had his nose in a book throughout the two and a half hour flight. I grinned to myself at the contrast between this small aircraft and the megatop which had carried me from the other side of the world. Suddenly I remembered the paper that John had found during his researches, about another plane. My uncle Will had made a report of having seen what he was quite certain was a small plane high above where he had been swimming with his son in Perth's Swan River on 2 March 1918. He wrote that he had observed it for about ten minutes, had seen quite a few planes in England and was sure this was not just a cloud. His son had seen the Kalgoorlie biplane in flight in WA and agreed with his father. A moment of excitement for them. 90 years on - we fly round the world without a thought and the moon landings are history. I went back to staring from the tiny window at the country below, deep red soil dotted with low scrubby trees and bushes and the pale clumps of what I guessed was the dreaded spinifex grass. Determined to get you one way or the other, the narrow leaves are needle sharp at the tips and it has equally vicious barbed spikelets. I had been warned about this menace. Just as we were putting on our seatbelts ready for the descent my neighbour closed his book, looked around and grinned a greeting. He was probably surprised at a woman on her own flying to Newman, not the usual tourist destination. I think I was the only one on board as most of the passengers would have been returning to work after the weekend and probably connected with the iron mining industry. The young man asked if I were staying in Newman. So I told him the purpose of my trip, to his growing delight and my growing excitement. He loved the Pilbara, you could see it in his eyes, and he assured me that I would too. He was so right.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

It was now dark, the rumble of the plane's engines had subsided, people were dispersing. And I was in the Pilbara. I had originally booked the mid-day plane so as to arrive in the afternoon, in daylight, as the plan was to meet John and Ruth, who would have come straight from their week-long bird survey further south, do some quick shopping to replenish their food stores and then go off into the bush to find somewhere to camp. But at home in England doing a last minute check on the Qantas website I found they had cancelled my flight up to Newman. There was little time left to notify my friends as they were about to start off on the bird trip. Phoning Qantas, I found that I was rebooked on a flight which would get me into Newman about 6 p.m. They just hadn't got round to telling me! I quickly emailed John with the news and had to leave him with the task of finding beds for us for the first night as prospecting in the outback for a suitable piece of ground could be a bit tricky in the dark. After a good supper at the Capricorn Roadhouse just outside Newman we were ready for bed. John had booked cabins for us there, basic, but who needed more? And the scrambled egg was great. Next morning, bright and early, we breakfasted then went into town so that Ruth could stock up on supplies. That done, we had a good look round the little museum in the Tourist Office - I bought an iron nugget as a memento - then at the outside exhibition where there was a good display of great old, rusting machinery once used in Mount Whaleback iron mine nearby. The Haulpack above is one example. This was the first one used to transport iron ore from the mine to the railhead. John joked that I would probably want to climb all over it (could he read my mind?) but I restrained myself and finally it was into the Toyota for a short drive up to the top of Radio Hill, just outside Newman. The girl in the tourist office had recommended this when I emailed for information about the town. She was right - the view over the hundreds of miles of outback was unbelievable. I drank it in, my gaze moving slowly from side to side at the great, glorious space. My friends had told me WA was big, sending me a picture showing half of Europe nestled inside it, and my response was that, yes, I do remember noticing that as a kid when I saw it in my atlas. But now the panorama was right in front of me, first taste of what was to come.

Views from Radio Hill, Newman

Eventually we drove back down the hill and returned to the Capricorn Roadhouse to refuel both ourselves, by way of a good lunch, and the ute. Then at last, all preparations completed, we started our journey of exploration in earnest, south down the Great Northern Highway. In a little while John turned off the road and down the bank to have a look at the dry bed of the Fortescue River. This was the first of several great wide river beds that I was to see, mostly completely devoid of water but all transformed in the wet season into rushing torrents flooding surrounding land and often driven by the cyclones coming ashore over to the west. Fortscue River road bridge

We carried on down the highway until we met the Jigalong turn-off. After a distance on that John went off-road into the bush, looking for the faint wheel marks which meant reasonably steady ground ahead on which to drive. I drew a deep breath as my heart beat faster.... we were going to search for the old telegraph station at Mundiwindi where Will had worked for a while. There was no way of knowing what, if anything, we would discover but it was going to be an absolutely unforgettable time trying. I knew that.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

John had acquired a permit under Section 31 of the Aboriginal Affairs Planning Authority Act 1972 (to give it its full title) for we three named individuals to enter and remain on the aboriginal reserve for 3-5 September 2007. But he had also had to obtain the permission of the Weelerrana station owner to go on to his land, where we now were. That is a must for various reasons apart from the obvious one of ownership. Going into the bush means you are on your own, and must be prepared in every way possible for any mechanical or medical emergency that may arise, as well as carrying fuel, food and as much water as there is room for. But if problems arise that you really cannot fix, it is the owner of the station who is going to have to turn out and find you.

Another reason is that they may be about to muster the cattle. My uncle Will, in one of his letters from Mundiwindi to my mother, had described an occasion in which drovers passing through with about 750 cattle on their 500 mile journey to the railhead, had settled for the night a mile or two away, when some small sound startled the animals and they "rushed stark mad like lightening", smashing bushes and trees before them. If one fell it was pulp in a few seconds. He described the superb horsemanship of the drovers as they headed them off, and said it was a terrifying spectacle in the moonlight but he felt quite safe as the house was about four feet off the ground. So being around at mustering time would not be advisable, in fact you would not get permission. Nowadays, of course, helicopters have replaced many of the drovers. The station owner had given John the approximate co-ordinates of the old building, but he had not been around there for some time and did not know what we would find. So there we were, off road and in the bush, just stunted trees and bushes and, of course, spinifex, all set against the rusty red soil. A dusty soil that covered everything. You put up a finger to scratch an itch and felt it on your skin, and at night when you moistened a flannel with a precious drop of water to make a pretence of washing your face or at least wiping your eyes, the result was a rust coloured flannel. It was nearing the end of winter and the temperature was already well into the 30's. And the silence - apart from bird calls and our own voices there was just no sound. I loved it from the very first moment and in some very odd way felt I belonged - no feeling of strangeness in unfamiliar territory. It just felt right. John's driving was incredible. He could see faint wheel tracks that could have been months old, so rarely did anyone pass that way - only idiots looking for telegraph stations. The number of times we would charge straight at clumps of spinifex two or three feet high because John had discerned two spaces between the clumps just a little wider than others and which meant to him two wheel tracks. I learnt to read the ground a little too, after a bit. Then there were the gullies, sometimes only a few feet wide, so that you felt the vehicle ought to be made of rubber and bend in the middle as the front started the upward climb while the rear was still trying to touch bottom. But inch by careful inch, lurching from side to side over rocks we would make it, every time. I hung on and just hoped I'd shut the door securely on my side. John and Ruth spend much of the winter months in the bush and his calm attention to where he put the vehicle inspired complete confidence. After much muttering, consulting of maps and the GPS receiver stuck precariously on the dashboard, to-ing and fro-ing we suddenly emerged into a clearer area on the edge of the Little Sandy Desert. Ahead of us were two large, ramshackle buildings.

Jumping out, I stared - at the old Mundiwindi Telegraph Station, not knowing whether to burst into tears or shout eureka! In the event I did neither, just felt stunned that this place with the odd sounding name which my mother had spoken of when I was a child, was now here right in front of me. I could see it, touch it, look into it. Even now, two years later as I write, the emotions flood back and I have to pull myself together and swallow hard.

Doors into the rooms were missing or hanging wide, no glass in the window frames - but it was there. It was too unsafe even to venture on to the veranda but I leant against it staring into the empty rooms and telling myself that here it was that Will had sat, writing those long letters in 1925-6 to his young sister, my mother back in England, letters that now sat in my desk drawer on the other side of the planet, still in their envelopes postmarked Mundiwindi. The Battye Library in Perth are interested in acquiring them but I cannot let them go - not yet.

Wandering around, John found the old windpump lying on the ground with a couple of what had presumably been water pipes nearby, and to my delight painted on the metal structure of the windpump was PM/MUNDIWINDI, still clearly visible. The station had, in fact, been in use up to the 1960's, long after Will had been there. Behind the buildings was still one of the telegraph poles with a piece of dangling wire that so long ago had hummed with messages.

The old windpump

Disused telegraph pole

Memories surfaced of when my mother had told me as a child of this brother of hers who had gone to Australia and to a place with the strange name of Mundiwindi, along with other more recent ones when John had first started his research for me and looking at the satellite maps on the Web I had found this obscure little place in the middle of nowhere, long before I had any thought of going to Oz.

I thought of the small, round tobacco tin I had in which Will had sent home some sample rock specimens, the address label still clearly postmarked Mundiwindi. Inside the tin remained a layer of dull red Pilbara soil - I looked down at what was at my feet. I wrestled with these memories to overlay them with the fact that they need no longer be just things my mother had told me. I looked around at the scrub, up at the intensely blue sky, felt the heat on my back, looked into the rooms again. Yes, I was there. My thoughts turned to the descriptions in Will's letters - I could see him that night, standing out on this veranda in the moonlight watching the terrifying spectacle of the cattle stampede, admiring the efforts of the drovers as they got things back under control. I saw the clouds of flies of all sorts making life a misery, and of one particularly vicious one - the bung-eye - which bit like lightning usually in the corner of the eye which immediately puffed up "like an egg". Will said that he had never been bitten by one but they "trim some of the natives up". Then there were the iguanas, the bungarra lizard which made very good eating and tasted like smoked haddock!

And the smaller, beautifully marked lizards, some very tame and of which he wrote " ... one at this very moment is catching flies on the wall of the room and lives in the house, a dear little fellow and so tame and only about 3 inches long but springs like lightning at flies (he's very welcome)." Which room was he in when he wrote that?

Small lizard at the side of the road

We had to leave eventually, of course, and climbed into the ute. I looked back, aware that it was highly unlikely that I would ever see that old building again. The images had been captured in my camera but they were to show my friends when I told them of my travels. For myself they were

hardly necessary - it was all safe in my mind's eye, images that could not be erased. We drove away from Mundiwindi, but so much more of this great trip was still to come, places that I had never thought to see, experiences that I had never thought to have.

THEY SANG FOR YOU - (Aborigines called the telegraph "The singing lines".

You worked up the lines, at Yinculya I found you; roamed in the outback - I followed your trail.

Marble Bar gave you this rosy streaked jasper, heat of the desert locked deep inside,

serpentine glittering with asbestos threads,

dull jade of copper veins, amber-toned beryl, fools’ gold to deceive. But there at the bottom my tin hides a nugget - true gold to enslave.

Your letters drew pictures of cattle - stampeding, pounding the bushes to pulp, the lizards, the sand-flies, scorpion and bull-ant pulsate in the pages that spell out your world.

As you worked so you loved it, this wild land that held you. Meekatharra, Kalgoorie, Pilbara, Mundiwindi, Eucla on the edge of the Nullarbor Plain – names spill from my lips as my faltering steps quicken but the tracks from your camels are lost in the swallowing sands.

Lines trembled with words, singing… mile into mile. The broad brim of your hat shaded eyes that were squinting to trace the bisection of white heated sky, till horizon completed the angle and measured your day.

They sang… you listened, testing the note. Now I sing… for I hear.

Ivy Collins

|